From the CIO's Desk > July 2024

By Prabhu Palani (Chief Investment Officer)

The Coming Bull Market

Most market prognosticators claim to be long-term; few have the luxury of being so. This is not a fault of the prognosticators but a reflection of the time horizons of their audience. Very rarely does one have the luxury of looking at the world beyond a quarter, a half-year, or even a year. The fortunate few who manage pools of capital that are long-term (those who manage pension plans, university endowments, etc.) are afforded the luxury of looking out over the immediate horizon, watching distant ships slowly disappear, and pondering questions such as the curvature of the earth’s surface.

When we think of the market (collectively stocks, bonds, commodities, and other such instruments), we often focus on factors like corporate earnings, interest rates, inflation, geopolitical issues, valuations, and investor sentiment. These are critical factors in assessing the health and viability of our current investments as well as future moves. As important as these factors are, once in a generation or two, seismic shifts occur in a nation’s history that must be reckoned with, which can have profound impacts on our capital well-being beyond the factors listed above. In fact, the way these shifts influence the factors can only be roughly measured, but their impact cannot be denied. We shine a spotlight on one such directional change in this essay.

In June of this year, the US Supreme Court passed two landmark judgments. Firstly, on the 27th, in SEC v. Jarkesy, it ruled against the SEC, and on the 28th, it overruled the so-called Chevron doctrine in two separate cases, Relentless v. Dept of Commerce and Loper v. Raimondo. We shall, in turn, consider each of these decisions.

After the Wall Street crash of 1929, Congress passed laws to strengthen investor protections: The Securities Act of 1933, The Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. To enforce these Acts, Congress created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC can bring an enforcement action in a federal court and, following the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, has the further ability to impose civil penalties in-house without the right to a jury trial. In the instant case, the SEC used Dodd-Frank to levy a civil penalty against Jarkesy, an investment adviser, for alleged violations of federal securities laws, without the right to a jury trial. In its ruling, the Supreme Court held that the SEC’s ruling violated Jarkesy’s Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roberts cited the importance of the right to a jury trial as being so significant that representatives of the First Continental Congress demanded that the English Parliament respect the “great and inestimable privilege of being tried by their peers of the vicinage…” and “when the English continued to try Americans without juries, the Founders cited the practice as a justification for severing our ties to England.” In her dissent, Justice Sotomayor says, “the majority’s decision, which strikes down the SEC’s in-house adjudication of civil-penalty claims… effects a seismic shift in the Court’s jurisprudence.” More on this later.

In the two cases overturning the Chevron doctrine, which arose from a 1984 ruling in Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council and which required courts to recognize permissible agency interpretations, the Supreme Court held that “courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous; Chevron is overruled.” In her dissent against the majority’s view and in support of an agency’s right to create rules, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that “Congress …cannot… write perfectly complete regulatory statutes” and that the Chevron doctrine, “has become part of the warp and woof of modern government, supporting regulatory efforts of all kinds—to name a few, keeping air and water clean, food and drugs safe, and financial markets honest.”

Why are these Supreme Court rulings in June of 2024 so important? And why do we quote the two dissents by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan? The heart of the matter is not the $300,000 fine levied on Jarkesy or the reimbursement of fishery license fees in the other two cases. Both rulings strike at the very heart of regulation and the government’s authority to interpret rules and regulations. As is obvious from the dissenting justices’ opinions, these cases will have far-reaching impacts on the ability of the SEC and other government agencies to interpret, regulate, and enforce laws.

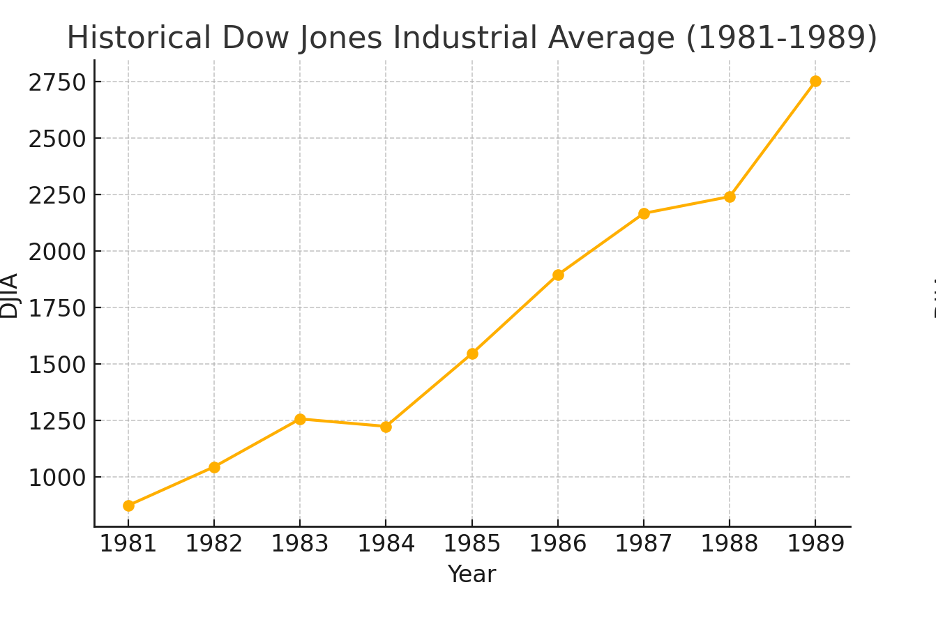

We have now entered the dawn of a new era of deregulation. This is not a political or social essay, and we abstain from discussing the societal and equity effects of deregulation. What concerns us is the impact of deregulation on the markets. Deregulation is decidedly business-friendly and entrepreneur-friendly; it has the potential to reduce government oversight, lower costs of compliance, encourage competition by lowering barriers to entry, and make it easier to start and manage a business enterprise. It also has the potential to unleash market spirits. In modern times, we often think of the Reagan era as one that promoted deregulation, with efforts to deregulate airlines, banking and financial services, utilities, environmental, and labor regulations. At the start of Ronald Reagan’s presidency in 1981, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 875, and when he left office in 1989, it was almost 2400, a multiple of almost 2.75x.

Why should we think of these two judgments as heralding a new era of deregulation? Simplistically speaking, conservatives favor less government and therefore deregulation. Our Supreme Court has a 6-3 conservative majority, which was also reflected in the June 27th and 28th decisions (in the Loper case it was 6-2 with Justice Jackson taking no part). With the Court’s majority unlikely to be altered by forces favoring greater regulation and government control, we can expect more decisions in the years ahead that limit the scope of governmental rules and regulations. Stare decisis, or judicial precedent, may no longer support those who have relied on historical decisions to support their liberal stance. In his concurring opinion in Loper v. Raimondo, Justice Gorsuch argues that “stare decisis is not an inexorable command.” To support his view, he quotes no less than Abraham Lincoln, who, in his debates with Stephen Douglas, refused to accept that “any single judicial decision could fully settle an issue…”

The implications for our markets can be extremely profound. The Dow Jones Industrial Average recently crossed 40,000. A Reagan-era-like return would take it to approximately 109,000 at the end of the next two presidential terms. Arguably, the Reagan-era tax reforms helped the market as well, and we may need support from such fiscal policy to propel the markets to dizzying heights. Airlines, banking and financial services, energy, transportation, and telecommunications sectors may all benefit from decreased regulation and greater innovation, while businesses that support environmental protections such as alternative sources of energy, energy transition, and climate change may suffer. This decade or perhaps multi-decade view does not preclude the possibility of market volatility, recessions, market corrections, or even a steep bear market. Such market movements are the natural outcome of economic cycles, system shocks, black swans, geopolitical risks, and technological disruptions. But as the pendulum of regulation swings to the side of absence, we can expect a gradual unfolding of the gilded era of The Great Gatsby. Ceteris paribus, pools of capital that remain long equity beta and have the luxury of a very long horizon can ride this wave of economic prosperity.

Prabhu Palani

References

The Supreme Court’s opinion in SEC v. Jarkesy Et Al, decided June 27th, 2024 https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/22-859_1924.pdf

The Supreme Court’s opinion in Loper Bright Enterprise Et Al v. Raimondo, Secretary of Commerce, Et Al, decided June 28th, 2024 https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/22-451_7m58.pdf

Supreme Court Strikes Down Chevron, Curtailing Power of Federal Agencies by Lowe, Amy, June 28th, 2024 https://www.scotusblog.com/2024/06/supreme-court-strikes-down-chevron-curtailing-power-of-federal-agencies/